In the 1960s, an American scientist and entomologist (a person who studies insects) interested in plant-insect interactions came to Costa Rica as part of a Tropical Ecology course. From that start as a student, Dan Janzen has dedicated almost 60 years to understanding the insect diversity of the dry forests of the Guanacaste province, eventually helping to establish the Area de Conservación Guanacaste (the ACG, Guanacaste Conservation Area, stretching from marine reserves in the Pacific ocean to the tropical rainforest on the backside of the Rincon de la Vieja volcano. Along the way he established the Guanacaste Dry Forest Conservation Fund to support this new conservation area, and initiated an ambitious effort to “barcode” every species of moth and butterfly in the Area. Barcoding involves sequencing a small area of the Cytochrome-C gene and using the sequence of nucleotides in the same way one would use a scannable barcode, as a distinctive identifier that is species specific.

We were told that in the 1970s Dan was laid up by an accident, and noticed that many of the more elusive moths were attracted by the light he worked by at night. From that observation emerged a concerted effort to use black lights (UV) and regular lights shining on sheets to attract moths and other nocturnal insects. This method of surveying suggested that this area of Guanacaste had about 15,000 species of butterflies and moths (collectively, Lepidopterans).

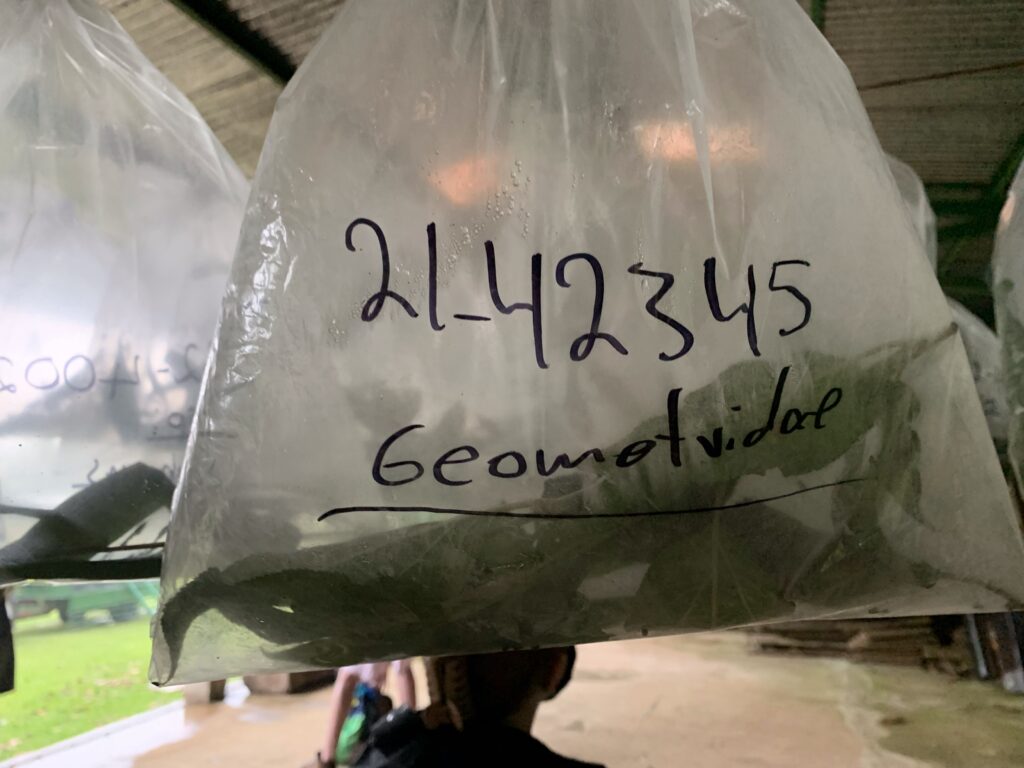

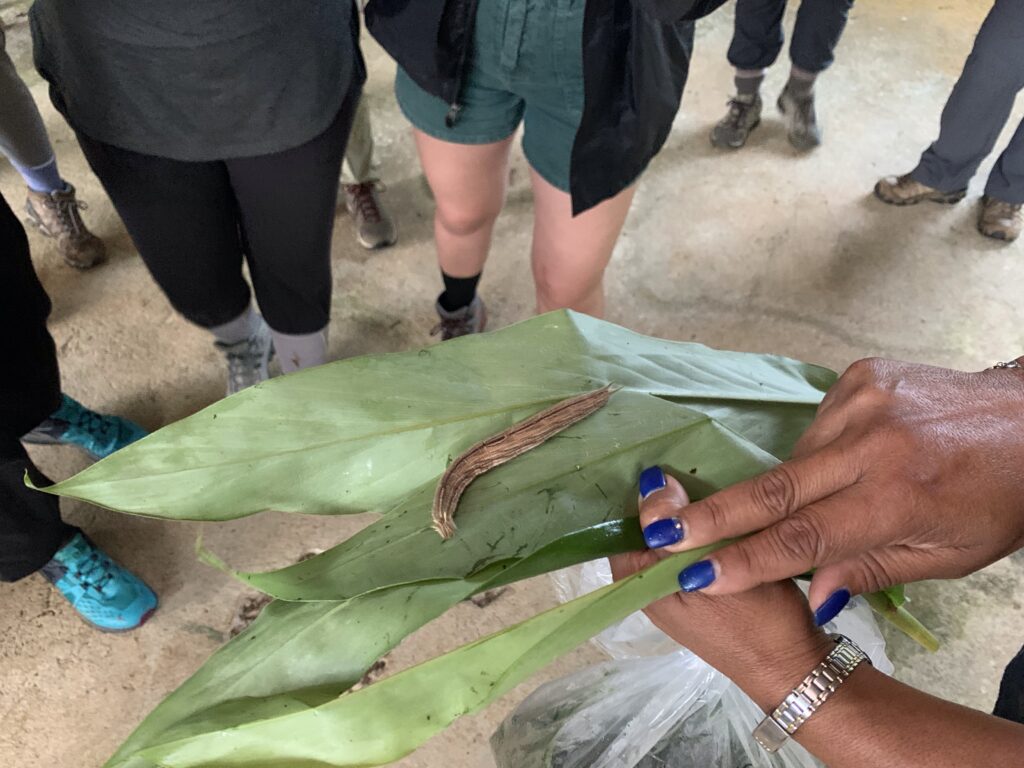

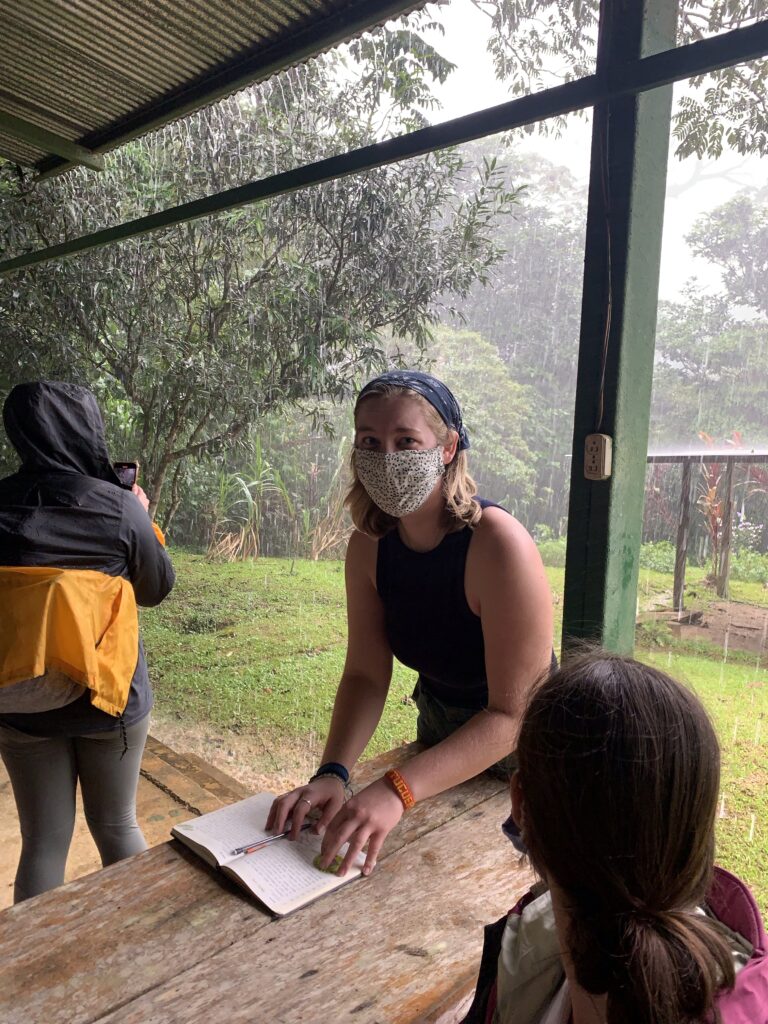

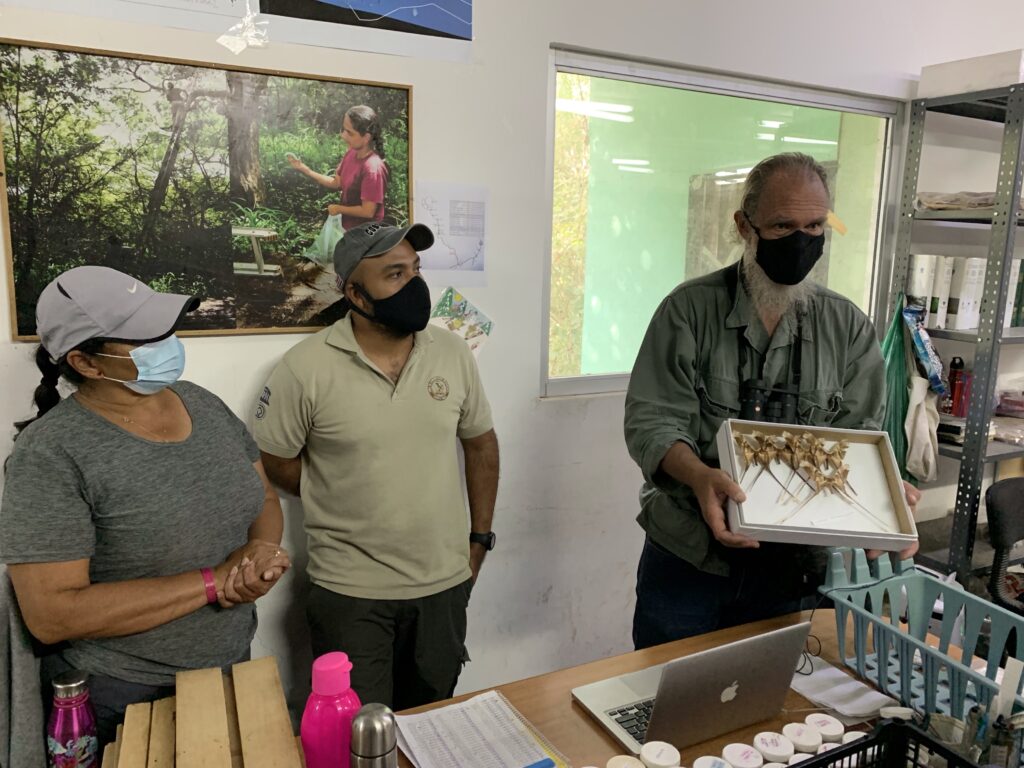

But documenting all the lepidopterans in ACG would be a huge job, so Dan set up a community project, funded by the Conservation Fund and research grants, that hired knowledgeable local people to collect the caterpillars, document exactly where they came from, raise them in bags on the foliage they were found on, photograph them professionally, put all this information into a computer database, and when they metamorphose into adults to send the adults to the central research station at Santa Rosa. Now there is a network of 15 research stations spread throughout the ACG, each staffed by professionally trained and equipped “parataxonomists” (like a paramedic, these are front-line people who provide the specimens and data used by PhD-level taxonomists). We were fortunate to meet 4 of them at the Caribe Biological Station in the rain forest a few miles from where we spent 3 nights at Finca La Anita (a chocolate farm owned and run by Ana and Pablo).

The parataxonomists with whom we spoke were very positive about the program, and proud of their work as scientists and conservationists. Most of them never finished high school, but were trained by Janzen’s Bio-Lep program and equipped with all that they needed to do the work—including top of the line computers, cameras, and transportation. They spoke appreciatively of Janzen “opening the world” to them.

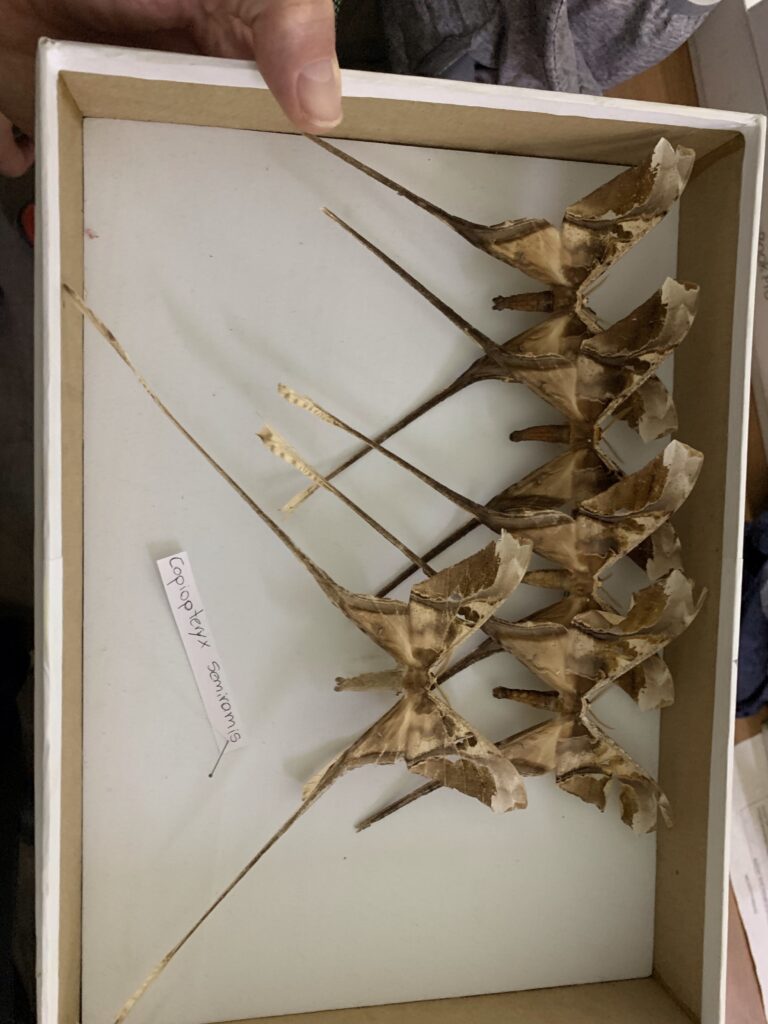

Their first job is to connect the larvae to the adult. With metamorphosis, obviously they look nothing alike, and for many of the adults their larval stage was unknown before this. Thus the careful effort to raise the caterpillars to adulthood.

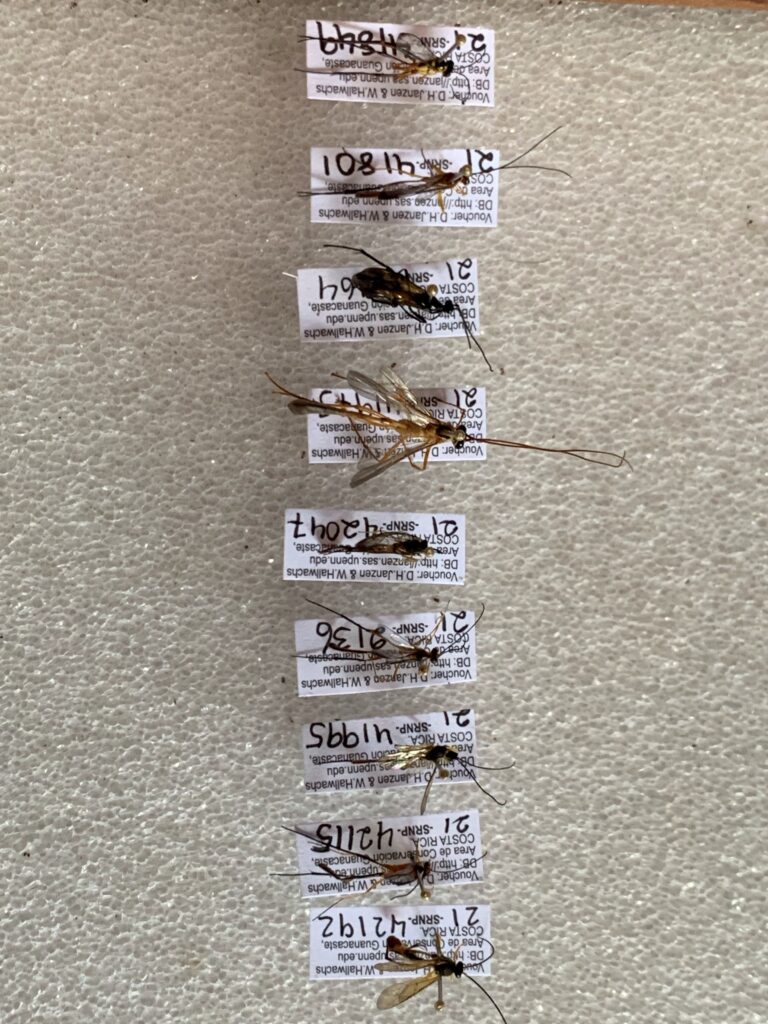

When we visited Santa Rosa station we saw where the adult moths and butterflies ended up. There, the moth is killed, a hind leg is pulled for DNA extraction to be used for barcoding, and the adult dried for inclusion in collections at the University of Costa Rica and the Smithsonian Institution. We were fortunate to get as a guide for this part of the story a student of Dan Janzen’s and a PhD scientist and educator who has been working in this area for over 30 years, “Señor Frank.” (For privacy reasons I’m not including last names.)

When asked what changes they’d seen in the 20+ years that some of them had done this work, Carolina (at Caribe station) became very animated about the changes they’d seen, laying the blame squarely with el cambio climático. Where 10 years ago they’d get 10-30 samples (caterpillars) per day, now they’re lucky to find 10. Many species they just don’t see anymore, or only find them at higher-elevation stations where they never used to appear. This vertical migration is one way that species can find the conditions they prefer—until they run out of mountain. The timing of the rains has changed; before the seasons were well marked, but now plants are blooming at times not useful to insects. It was one more personal testimony about how climate change is affecting life in this part of Costa Rica.

Over the years, Dan Janzen and his team of parataxonomists have documented the crash of many populations of butterflies and moths, casualties of the ongoing climate catastrophe.